Last week in Santiago, Chile, I had the tremendous opportunity to give a keynote speech at the 4th annual workshop of the Millennium Nucleus on the Evolution of Work (M-NEW), of which I am also a senior international member. This interdisciplinary workshop brought together labour scholars from various parts of Latin America and beyond. I really liked the inspiring talks and the friendly and stimulating interactions with colleagues.

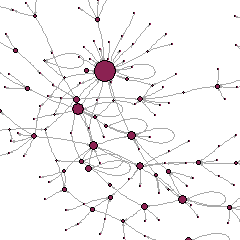

My own talk drew on my multi-year research programme on the crucial yet invisible human labor behind the global production of artificial intelligence. I first examined the evolution of this form of work over the last two decades, demonstrating that while its core functions in the development of smart systems have remained consistent, the scope and volume of such tasks have expanded significantly. I then analyzed the organization of this labour at the intersection of three trends in recent globalization: outsourcing, offshoring, and digitalization. These dynamics account for the marginalization of these workers within the tech industry and the relocation of their labor to lower-wage countries. Based on these insights, I described four cases—Venezuela, Argentina, Brazil, and Chile—highlighting the diverse effects of local conditions. I concluded by identifying emerging scientific and policy challenges, particularly concerning the recognition of skills, and the place of the informal economy.

The following week, still in Santiago, I was excited to participate in the kick-off meeting of the new research project SEED (“Social and Environmental Effects of Data connectivity: Hybrid ecologies of transoceanic cables and data centers in Chile and France”), a collaboration between my research group DiPLab and another Millennium Nucleus, FAIR (“Futures of Artificial Intelligence Research”). SEED received joint funding from the ECOS-SUD programme (France) and ANID (Chile) to analyse the AI value chain, from its production and development to its impact on employment, use and environmental consequences, by studying the Valparaíso-Santiago de Chile and Marseille-Paris axes.

My presentation introduced the concept of the ‘dual footprint’ as a heuristic device to capture the commonalities and interdependencies between the different impacts of AI on the natural and social surroundings that supply resources for its production and use. I framed the AI industry as a value chain that spans national boundaries and perpetuates inherited global inequalities. The countries that drive AI development generate a massive demand for inputs and trigger social costs that, through the value chain, largely fall on more peripheral actors. The arrangements in place distribute the costs and benefits of AI unequally, resulting in unsustainable practices and preventing the upward mobility of more disadvantaged countries. The dual footprint grasps how the environmental and social dimensions of AI emanate from similar underlying socio-economic processes and geographical trajectories.