How do digital platforms affect the concrete functioning of markets that pre-existed them? Platforms are intermediaries and it was initially thought that they could solve any mismatches between supply and demand. In the restaurant sector, the hope was that they would seamlessly connect diners with available tables and help restaurants fill their rooms. Yet traditional booking methods remain, and many restaurants restrict the number of seats offered through platforms. A recent study, which I have just co-published with Elise Penalva Icher and Fabien Eloire, examines why.

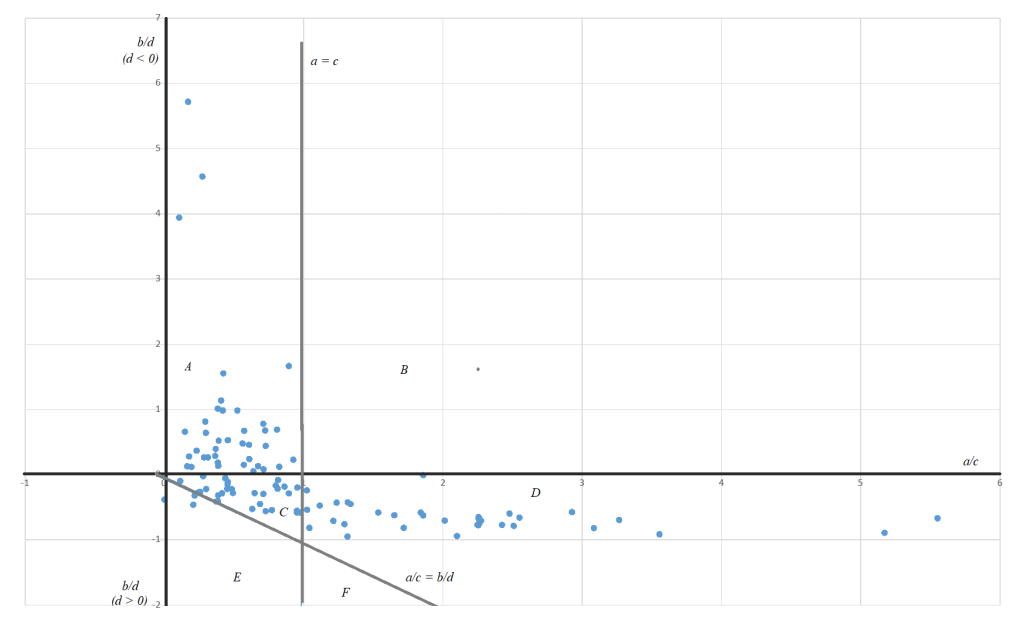

We borrow Harrison White’s famous producer market model, based on the idea that the key problem of a firm is to position itself in a market that consists of differentiated niches. Restaurants are not homogeneous, and they continuously scan the market to fine-tune their offer – from fine dining to bistro and pizzeria. They evaluate two main indicators: volume, which is relatively straightforward, and quality, which is harder to gauge as it depends on subjective customer perceptions. Platforms break through this limitation by publishing consumers’ reviews and aggregating them into ratings. They provide “digital glasses” that reveal quality alongside volume.

The study investigates dine-in services in Lille, France, in the case of a widely adopted booking and review platform. Methods include participant observation, interviews, web-scraping, and quantitative analysis of business data.

Findings highlight three key effects. First, an amplification effect: platforms enable restaurants to see “like a market,” not just through their own customers but also through competitors’ clients. Second, a normalization effect: platform use pushes firms to standardize their offers, fostering similarity without complete homogenization. Third, a duration effect: sustained platform participation depends on quality positioning, although many restaurants exit after a few years, partly in response to platform dominance. These dynamics suggest a broader rationalization process in which platforms make market observation more systematic and efficient.

This perspective nuances common claims about platforms as market “revolutions.” The study finds no evidence that platforms improve consumer–producer matching. None of the interviewed restaurateurs feared empty tables, and some deliberately withheld capacity from the platform to accommodate walk-ins or phone bookings. Overemphasizing intermediation, earlier research may have overlooked subtler effects. The key function of platforms does not always have to be matching. They can play diverse and even unbalanced roles on a single side of the market, without striving toward a competitive supply-demand equilibrium.

The analysis also reaffirms the validity of White’s model. Originally designed for settings where firms observed only volumes, the model still applies when platforms disclose quality through reviews. Its insights hold across different technological contexts.

Finally, the study underscores the limits of using platforms as sources of research data. We relied on platform data, but we faced gaps: available data are partial because platform objectives differ from research needs, and algorithms remain proprietary. This raises concerns, as platforms exert broad societal influence while controlling critical information.

Overall, the research advances understanding of how platforms affect business practices, in this case restaurants. It contributes to critical scholarship that recognizes the novelty of platform intermediation while tempering claims about its benefits.

The study is available in open access here.