Within the Horizon-Europe project AI4TRUST, we published a first report presenting the state of the art in the socio-contextual basis for disinformation, relying on a broad review of extant literature, of which the below is a synthesis.

What is disinformation?

Recent literature distinguishes three forms:

- ‘misinformation’ (inaccurate information unwittingly produced or reproduced)

- ‘disinformation’ (erroneous, fabricated, or misleading information that is intentionally shared and may cause individual or social harm)

- ‘malinformation’ (accurate information deliberately misused with malicious or harmful intent).

Two consequences derive from this insight. First, the expression ‘fake news’ is unhelpful: problematic contents are not just news, and are not always false. Second, research efforts limited to identifying incorrect information alone, without capturing intent, may miss some of the key social processes surrounding the emergence and spread of problematic contents.

How does mis/dis/malinformation spread?

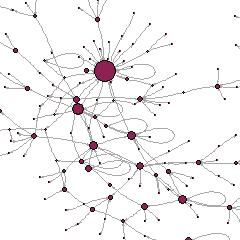

Recent literature often describes the characteristics of the process of diffusion of mis/dis/malinformation in terms of ‘cascades’, that is, the iterative propagation of content from one actor to others in a tree-like fashion, sometimes with consideration of temporality and geographical reach. There is evidence that network structures may facilitate or hinder propagation, regardless of the characteristics of individuals: therefore, relationships and interactions constitute an essential object of study to understand how problematic contents spread. Instead, the actual offline impact of online disinformation (for example, the extent to which online campaigns may have inflected electoral outcomes) is disputed. Likewise, evidence on the capacity of mis/dis/malinformation to spread across countries is mixed. A promising perspective to move forwards relies on hybrid approaches mixing network and content analysis (‘socio-semantic networks’).

What incentivizes mis/dis/malinformation?

Mis/dis/malinformation campaigns are not always driven solely by political tensions and may also be the product of economic interest. There may be incentives to produce or share problematic information, insofar as the business model of the internet confers value upon contents that attract attention, regardless of their veracity or quality. A growing, shadow market of paid ‘like’, ‘share’ and ‘follow’ inflates the rankings and reputation scores of web pages and social media profiles, and it may ultimately mislead search engines. Thus, online metrics derived from users’ ratings should be interpreted with caution. Research should also be mindful that high-profile disinformation campaigns are only the tip of the iceberg, low-stake cases being far more frequent and difficult to detect.

Who spreads mis/dis/malinformation?

Spreaders of mis/dis/malinformation may be bots or human users, the former being increasingly controlled by social media companies. Not all humans are equally likely to play this role, though, and the literature highlights ‘super-spreaders’, particularly successful at sharing popular albeit implausible contents, and clusters of spreaders – both detectable in data with social network analysis techniques.

How is mis/dis/malinformation adopted?

Adoption of mis/dis/malinformation should not be taken for granted and depends on cognitive and psychological factors at individual and group levels, as well as on network structures. Actors use ‘appropriateness judgments’ to give meaning to information and elaborate it interactively with their networks. Judgments depend on people’s identification to reference groups, recognition of authorities, and alignment with priority norms. Adoption can thus be hypothesised to increase when judgments are similar and signalled as such in communication networks. Future research could target such signals to help users in their contextualization and interpretation of the phenomena described.

Multiple examples of research in social network analysis can help develop a model of the emergence and development of appropriateness judgements. Homophily and social influence theories help conceptualise the role of inter-individual similarities, the dynamics of diffusion in networks sheds light on temporal patterns, and analyses of heterogeneous networks illuminate our understanding of interactions. Overall, social network analysis combined with content analysis can help research identify indicators of coordinated malicious behaviour, either structural or dynamic.