We’re hiring!

As part of a large, interdisciplinary European research project, we are seeking a motivated, open-minded student to join CNRS (specifically, the Centre for Research in Economics and Statistics, CREST) in Palaiseau, France, for three years.

The thesis aims to model the production and dissemination of ‘fake news’ in situations of uncertainty and socio-economic inequality. A rich sociological literature suggests that actors contextualise messages received and emitted as questions or answers, interpret them according to their recipients and senders, and assess their social acceptability within their own networks of relationships, taking into account their relative position. Building on this research, the goal is to identify the social processes underpinning misinformation-generating digital communications: collective identity, inequalities of status or authority, hierarchy of shared norms. This will enable interpreting the online social interactions through which actors collectively judge the (appropriate or inappropriate) quality of a message or information and then decide whether to relay or share it – and with whom. In particular, the thesis work will contribute to: 1/ drawing up a state of the art, mainly within sociology but open to the neighbouring disciplines which have also addressed these questions; 2/ illustrating and testing these theories through an empirical analysis of a digital database, mainly with quantitative methods, which may be enriched through a small complementary qualitative fieldwork; 3/ to contribute to the preparation of guidelines that help information professionals and policy-makers to detect the sources and modalities of emergence and propagation of misinformation.

The thesis will be done within the framework of the interdisciplinary project “AI-based-technologies for trustworthy solutions against disinformation” (AI4TRUST), funded by the European Union over the period 2023-2026, involving 17 partners (research institutions and media professionals) in 10 countries, and coordinated by Fondazione Bruno Kessler (Italy).

The AI4TRUST project aims to build a hybrid system, with advanced artificial intelligence solutions capable of cooperating with humans in the fight against disinformation. The new algorithms that will be developed in this framework, constantly checked and improved by human fact-checkers, will monitor multiple online social platforms in nearly real time, analysing text, audio, and visual contents in several languages. The resulting quantitative indicators, including infodemic risk, will be inspected under the lens of social and computational social sciences, to build the trustworthy elements required by media professionals.

CNRS contributes to the study of the sociological dimension of these issues, and participates in the project through its laboratories Centre Marc Bloch (CMB, Berlin), Centre de Sociologie des Organisations (CSO, Paris) and Centre de Recherche en Economie et Statistique (CREST, Palaiseau). In practice, the thesis will be carried out at CREST, and co-directed by representatives of the three laboratories involved in this AI4TRUST: myself, Emmanuel Lazega (CSO) and Camille Roth (CMB).

The successful candidate will have the opportunity to join a group of highly motivated scientists and practitioners from across the continent; to participate in collaborations with other teams working on the project in an interdisciplinary framework; to attend regular meetings with the project’s principal Investigator, the scientists and experts involved, and public decision-makers; to present and publish research results in international conferences and journals.

The ideal candidate has a good background in quantitative sociology or in a STEM discipline (e.g., mathematics, statistics, computer science) with a strong interest in societal issues and challenges. A very good knowledge of English, an interdisciplinary approach and the ability to work in teams are essential.

Candidates should apply on the CNRS portal, where they will also find more details.

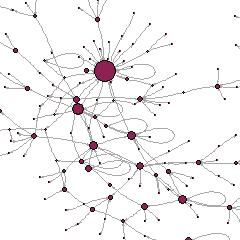

Just back from a stimulating summer school on social network analysis and complexity, organised in sunny Cargèse (Corsica). Lots of exciting talks on communities, network dynamics, and complex social structures, with a touch of genuine interdisciplinarity.

Just back from a stimulating summer school on social network analysis and complexity, organised in sunny Cargèse (Corsica). Lots of exciting talks on communities, network dynamics, and complex social structures, with a touch of genuine interdisciplinarity.