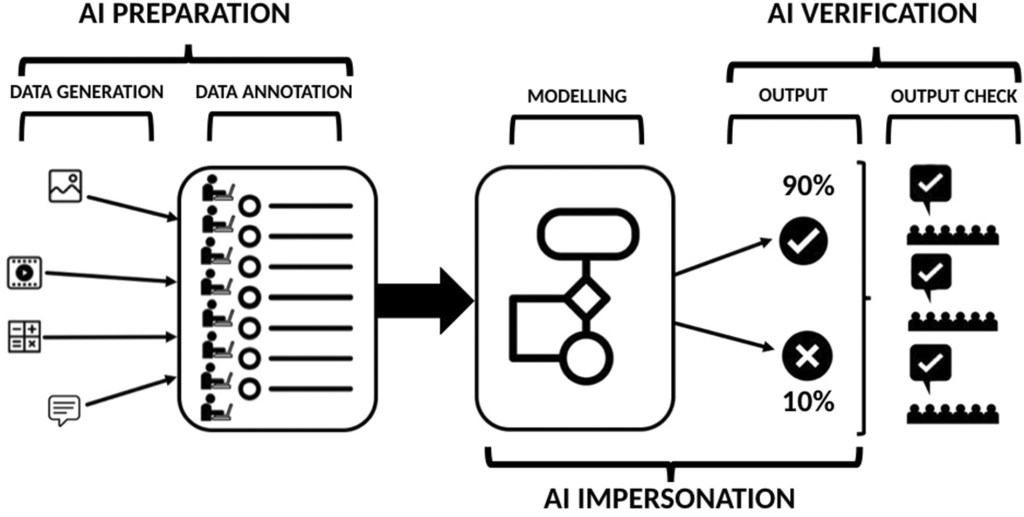

I presented today, at the WORK2025 conference in Turku, Finland, a paper on the human-in-the-loop systems that integrate human labor into the production of Artificial Intelligence (AI). Beyond engineers who design models, myriad “data workers” prepare training data, verify outputs, and correct errors. Their role is crucial but undervalued, with low pay and poor working conditions. Shaped by outsourcing and offshoring practices, the market for such services has grown steadily over time, with digital platforms acting as the main intermediaries between AI producers and workers. In their communication with clients, these platforms often emphasize that human workers provide nuanced judgment in complex tasks.

But who are the humans in the loop, and whose contributions count? Here, I focus on women’s participation and its evolution as the market expanded. Data work is theoretically well-suited for women, since it can be performed remotely from home. Besides, platforms generally do not share gender information, thereby limiting direct discrimination. One might thus expect women’s representation to be high. However, the statistical evidence is mixed. Across studies, the proportion of women data workers exceeds 50% only in four cases. Besides, reports sometimes differ for the same country, across platforms or at different moments in time. Looking at the lowest reported shares, then in no country except the US do women represent more than 40% of all data workers. Even in the US, recent data indicate that women constitute about half of the data workforce, down from 57-58% some years ago. Why are women underrepresented, and why does the pattern vary across countries?

The earliest explanation comes from P. Ipeirotis (2010), who analyzed Amazon Mechanical Turk, then the dominant platform. Most workers were from the US and India. In the US, data work paid too little to sustain a household and was often taken up by un- and under-employed women seeking supplementary income. In India, dollar-based pay was more attractive and often a main household income, drawing more men into the activity. Later, as the market expanded, this explanation appeared insufficient: the above maps show that not all rich countries have many female data workers, and some lower-income countries do. Yet, my data show a negative correlation: the larger the share of workers for whom data work is the main income source, the smaller the proportion of women. Ipeirotis’s hypothesis still holds but requires updating to today’s more competitive and globalized platform economy.

Platforms fragment work into tasks and assign them to individuals framed as independent contractors competing for access. Unlike traditional firms, workers do not collaborate but face intense competition. Outcomes vary by national context. In countries facing stagnation or crisis, such as Venezuela, international platforms offer a rare source of income for highly qualified workers. Competition becomes fierce, and “elite” workers – often young men with STEM backgrounds – dominate. Women are disadvantaged, either due to fewer technical qualifications or because care responsibilities limit their ability to invest in building strong platform profiles and reputations. By contrast, in more dynamic economies such as Brazil, local job markets absorb highly skilled professionals, leaving platform work to more disadvantaged groups. Here, women with family duties are more visible. Thus, platform demographics reflect national conditions: in poorer or crisis-stricken countries, men from the educational elite seek career advancement, while in richer countries, women (especially mothers) take on such work primarily to supplement household income. Women may be equally educated, but they often lack the time to cultivate advanced STEM skills. As platforms demand longer and more specialized tasks, men increasingly gain the upper hand, crowding women out—even in countries where they were once the majority.

Platform design ignores these dynamics. Workers are treated as abstract entities, stripped of the socio-economic and cultural contexts that shape real inequalities. Competition, combined with local conditions, deepens gender gaps. Interventions must therefore consider gender disparities. Otherwise, they risk reinforcing inequalities. Supporting women’s access to data work—particularly those constrained by family responsibilities—can contribute to more balanced labor participation and ensure that AI benefits from a broader diversity of human input.