The impacts of artificial intelligence (AI) on the natural and social surroundings that supply resources for its production and use have been studied separately so far. In a new article, part of a forthcoming special issue of the journal Globalizations, I introduce the concept of the ‘dual footprint’ as a heuristic device to capture the commonalities and interdependencies between them. Originally borrowed from ecology, the concept denotes in my analysis the total impacts on the natural and social surroundings that supply the resources necessary for AI’s production and use. It is an indicator of sustainability insofar as it grasps the degree to which the AI industry is failing to ensure the maintenance of the social systems, economic structures, and environmental conditions necessary to its production. To develop the concept in this way, it is necessary to (provisionally) renounce some of the accounting flavour of extant footprint measures, allowing for a more descriptive interpretation. In my article, the dual footprint primarily serves as a mapping tool, linking impacts to specific locations and to the people and groups that inhabit them.

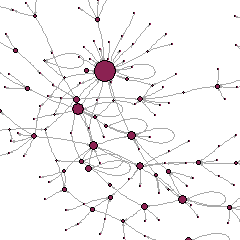

My analysis draws on recent research that challenges idealized narratives of AI as the sole result of mathematics and code, or as the fancied machinic replacement of human brains. The production of AI relies on global value chains which, like those of textiles and electronics, take shape within the broader context of globalization, its long-standing trends of outsourcing and offshoring, and the cross-country disparities on which it thrives.

The argument is based on two case studies, each illustrating AI-induced cross-country flows of natural resources and data labour. The first involves Argentina as a supplier to the United States, while the second includes Madagascar and its primary export destinations: Japan and South Korea for raw materials, France for data work. These two cases portray the AI landscape as an asymmetric structure, where the countries that lead the tech race generate a massive demand for imports of raw materials, components, and intermediate goods and services. Core AI producers trigger the footprint and therefore should bear responsibility for it, but the pressure on (natural and social) resources and the ensuing impacts occur predominantly elsewhere. Cross-country value chains shift the burden toward more peripheral players, obscuring the extent to which AI is material- and labour-intensive.

This drain of resources toward AI engenders adverse effects in peripheral countries. Mining notoriously generates conflicts, and data work conditions are so poor that other segments of society – from local employers to workers’ families and even informal-economy actors – must step in to cover part of the costs. The current arrangements thus fail to ensure their own sustainability over time. Additionally, the aspirations of these countries to leverage their participation to the AI value chain as a development opportunity, and to transition toward leading positions, remain unfulfilled.

The dual footprint can fruitfully dialogue with the critical literature that leverages the concepts of extractivism (for example, Cecilia Rikap‘s concept of “twin” extractivism) and dependency (as theorised for example by Jonas Valente and Rafael Grohmann). Its contribution lies mainly in the effort to operationalise the ideas of more abstract social theories, while also facilitating mutual enrichment between different literatures.

Read the full paper: subscription-protected or open-access preprint.

The paper was developed as part of an initiative on ‘The Political Economy of Green-Digital Transition‘, organised by Edemilson Paraná in 2024 at LUT University in Finland. Further, the idea that the environmental and social dimensions of AI production emanate from similar underlying socio-economic processes and geographical trajectories constitutes the foundation of SEED – Social and Environmental Effects of Data Connectivity, a new DiPLab project that investigates how data extraction and material extraction are deeply interconnected. It stems from a collaboration with Núcleo Milenio FAIR at the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile and compares data and material infrastructures in Europe and South America.