The work that fuels AI – from data labelling to content moderation, output checking, red teaming, and so on – is typically outsourced. Digital platforms that operate as online marketplaces play a pivotal role in making this possible. They extend outsourcing to individuals, removing the informational bottlenecks that previously limited it to (multi-person) firms. Platforms treat workers as independent contractors and do not guarantee labour rights. Job insecurity, income volatility, wage theft, and in some cases mental health issues, are common. However, cases of worker mobilisation remain rare. Why, and how can this be changed?

Barriers

A specific challenge that arises on platforms is the asymmetric distribution of work, with a relatively small number of users doing most tasks, and a long tail of minimally-active (or even inactive) people. The reason is that registration is (more or less) open but demand is variable, so that a worker must beat the competition to find tasks to do. This has two main implications. One is that from start, there is an incentive to see other workers as competitors rather than colleagues. The other is that it is difficult to motivate people in the long tail to take action: they are more likely to exit than to voice their grievances.

Lack of a shared worker identity is another crucial gap. Data work was initially portrayed as simple and straightforward, and even sometimes considered as a form of consumption or leisure. Many platforms carefully avoid even using the word ‘worker’, instead preferring terms like ‘Turkers’ (Amazon Mechanical Turk) or ‘Tolokers’ (Toloka). The very fact that workers themselves often take the rhetoric of simple tasks at face value, and struggle to see themselves as such, is indicative of their experience of disrespect, due to widespread misrecognition.

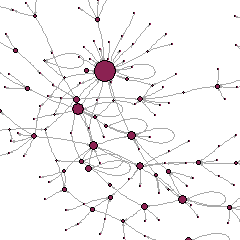

Juliet Schor writes that “platform earners are not only independent in a legal sense; they also typically do their work independently of other workers”. Technology enables extreme fragmentation of labour and rules out teamwork. Neither do workers ever meet their clients (technology producers), due to platform intermediation. In sum, platform data work isolates workers both from their peers and from other stakeholders (as the above picture cleverly represents). How to organise if you are alone?

Alternatives

In this context, it is useful to broaden our understanding of worker organisation. Beyond collective acts undertaken within an institutionalised framework, we should also embrace informal, unorganised and subtle actions, which can nevertheless lead to positive outcomes.

In crisis-stricken Venezuela, very large numbers of people started data work on online platforms to earn much-needed hard currency. Here, workers have leveraged their personal networks of family and friends to surmount the multiple obstacles posed by platform work. They never created any official organisation, and their actions would rarely qualify as forms of resistance. Some were mere attempts to limit losses in a harshly competitive environment. As researchers, we need to be mindful of cases in which, owing to an unfavourable context, workers prioritise the (short-run) need to counter local scarcity through online earnings, rather than any (longer-run) fight against unfavourable platform management. (More on this case here.)

Ways forward

There are nevertheless signs that successful strategies exist. Kenya is a rare example of organisation: data workers and content moderators in this country initiated actions that attracted international attention and, as in a virtuous circle, support. Of course, not all is easy for them, but Kenya is now a reference, an example for everyone else. This suggests that it is essential to give visibility to workers’ conditions and to any action they undertake to defend their rights.

The other lesson learned from the Kenyan case is that collaborations between multiple stakeholders can achieve a lot in supporting workers and triggering change. Not only established unions, but also researchers, policymakers, and activists in various NGOs (for example, engaged for personal data protection, against discrimination, etc.) can act as multipliers of the resources available to workers.