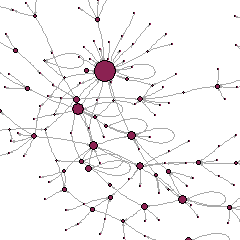

How many people do you know? How many friends do you have? You may have tried to count your contacts on Facebook or other social networking websites. You may even have felt a bit weird realizing that your “real” friends — those you can rely on — are just a handful. As unexpected it might seem, business professionals have this question in mind too: they want to get a sense of the potentially useable social capital of their associates and employees.

Social research has investigated this matter intensely and can offer insight. There are, in fact, two aspects to be considered: the size of personal networks and the effects of online communication on socialisation.

The size of personal networks

Let us first start with the size of personal networks. A milestone in this debate is the so-called “Dunbar’s number“, based on a 1992 study of Oxford anthropologist Robin Dunbar. The idea is that human cognitive capacities as measured by the size of the neocortex lead to a network size of around 148 (with some range of variation). The original study compared the size of the neocortex in various groups of primates and humans and referred to cohesive communities. The resulting limit indicates the number of people with whom one can maintain “stable” social relationships, i.e., know who each contact is, and how they are related to one another.

Other parts of the brain may be involved too, suggest neuroscientists: Lisa Barrett and her co-authors (2010) found a correlation between amygdala volume and social network size in humans. (I understand that the amygdala is the part of brain that regulates emotional responses and aggression, while the neocortex to which Dunbar referred is the part of the brain that presides higher mental functions.) (see this Blogpost for further information).

In social network analysis perspective, it is also important to define which social network we are measuring. Peter Marsden (1987) distinguished “core” networks from whole personal networks, pointing out that even when people have many friends, there are only a handful with whom they “can discuss important matters”. In this sense, core networks may not include more than five or six people. So if you thought you had very few friends, you shouldn’t feel weird after all… apparently the Portuguese have a saying, “You have five friends, and the rest is landscape.”

On the other hand, your full network also including mere acquaintances and weaker ties may be much larger than Dunbar’s: counts of full networks taken by Peter Killworth, H. Russel Bernard, Chris McCarthy and co-authors in the 1990s – 2000s went up to about 1500 for the average American. From these, they extracted more meaningful measures of networks that are really relevant for people’s daily lives and came up with other numbers: they found a mean personal network size of 290 (twice the Dunbar number!); more recently, Matthew Salganik and his co-authors (2010) have come up with an even larger size of 610 (twice Killworth’s number…).

Overall, an issue that emerges from many of these discussions is that cognitive capacities (however defined) matter primarily because they are associated with a basic limitation of all living beings –time is finite. Therefore, increasing the size of one’s personal network implies that less time is available for each contact: the size of the overall network increases, but the size of the core network doesn’t. Weak ties may gain at the expense of strong ties.