There are two main ways in which a discipline like sociology engages with artificial intelligence (AI) and is affected by it. In a previous post, I discussed how the sociology of AI understands technology as embedded in socio-economic systems and takes it as an object for research. Here, focus is on sociology with AI, indicating that the discipline is integrating AI into its methodological toolbox.

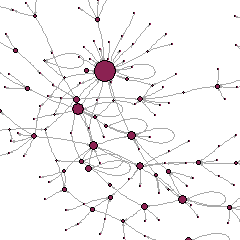

AI technologies were designed for other-than-research purposes, but they may be repurposed. The editors of a special issue of Sociologica last year stress that, ten years ago, digital methods presented similar challenges: for example, using tweets to make claims about the social world required us to understand how people used Twitter in the first place. We also needed to understand which people used Twitter at all, and what spaces of action the architecture and Terms of Use of this platform allowed. Likewise, using AI technologies can serve sociologists insofar as efforts are made to understand the technological (and socio-economic) conditions that produced them. Because AI systems are typically blackboxed, this requires, to begin with, developing exploration techniques to navigate them. For example, the plot below is from a recent paper that asked five different LLMs to generate religious sermons and compared the results (readability scores) by religious traditions and race. It finds that Jewish and Muslim synthetic sermons were constructed with significantly more difficult reading levels than were those for evangelical Protestants, and that Asian religious leaders were assigned more difficult texts than other groups. It is a way to uncover how models treat religious and racial groups differently, although it remains difficult to detect precisely which factors affect this result.

That said, how can AI help us methodologically? To answer this question, it is useful to look at qualitative and quantitative approaches separately. Qualitative research, traditionally viewed and practiced as an intensely human-centred method, may seem at first sight incompatible with it. However, use of computer-assisted qualitative data analysis (with tools such as Nvivo) is now common among qualitative researchers, though it faced some degree of scepticism at the beginning. Attempts to leverage AI move forward this agenda, and the most common application so far is automated transcription of interviews through speech recognition technologies. AI-powered tools make this otherwise tedious task more efficient and scalable. A recent special issue of the International Journal of Qualitative Methods maps a variety of other usages, less common and more experimental: for example, considering that even the best models for audio transcription are not as accurate as humans, LLMs appear as tools to facilitate and speed up transcription cleaning. There are also some attempts at using LLMs as instruments for coding and thematic analysis: for example, some authors have examined inter-coder reliability between ‘human only’ and ‘human-AI’ approaches. Others have used AI image generation like vignettes – as a tool for supporting interview participants in articulating their experiences. Overall, the use of AI remains experimental and marginal in the qualitative research community. Those who have undertaken these experiments find the results encouraging, but not perfect.

In quantitative research, some AI tools are already (relatively) widely used: in particular, natural language processing (NLP) to process textual data like corpora from the press or media. More recent applications leverage generative AI, especially large language models (LLM). Outside practices like literature review and code generation/debugging, which are common to multiple disciplines, three applications are specifically sociological and worth mentioning. First, in experimental research, there are some attempts to examine how the introduction of AI agents in interaction games shapes the behaviour of the humans they play with. As discussed by C. Bail in an insightful PNAS article, the extent to which generative AI is capable of impersonating humans is nevertheless subject to debate, and it will probably evolve over time. Second, L. Rossi and co-authors outline that in agent-based models (ABM), an idea is to use LLMs to create agents that are more capable of capturing a larger spectrum of human behaviours. While this approach may provide more realistic descriptions of agents, it re-ignites a long-standing debate in the field: indeed, many believe that increasing the complexity of agents is undesirable when emergent collective dynamics can emerge from more parsimonious models. It is also unclear how the performance of LLMs within ABMs should be evaluated. Shall we say that they are good if they reproduce known collective dynamics within ABMS? Or, should they be assessed based upon their capacity to predict real-world outcomes? Third, in survey research, the question has arisen whether LLMs can simulate human populations for opinion research. Some studies have tested this possibility, with mixed results. The most recent available evidence, in an article by J. Boelaert and co-authors, is that: 1) current LLMs fail to accurately predict human responses, 2) they do so in ways that are unpredictable, as they do not systematically favor specific social groups, and 3) their answers exhibit a substantially lower variance between subpopulations than what is found in real-world human data. In passing, this is evidence that so-called ‘bias’ does not necessarily operate as expected – LLM errors do not stem primarily from unbalanced training data.

These applications face specific ethical challenges. First, studies that require humans to interact with AI may expose them to offensive or inaccurate information, the so-called ‘AI hallucinations’. Second, there are new concerns about privacy and confidentiality. Most GenAI models are the private property of companies: if we use them to code in-depth interviews about a sensitive topic, the full content of these interviews may be shared with these companies, often not bound by the same standards and regulations in terms of personal data protection. Third, the environmental impact of these models is high, in terms of energy to run the system, water to cool servers in data centres, metal extraction to build devices, and production of e-waste. The literature on AI-as-object also warns that there is a cost in terms of the unprotected human work of annotators.

Another limitation is that is that research with Generative AI is difficult to replicate. These models are probabilistic in nature: even identical prompts may produce different outputs, in ways that are not well understood as of today. Also, models are constantly being fine-tuned by their producers in ways that we as users do not control. Finally, different LLMs have been found to produce substantially different results in some cases. Many of these issues are due to the proprietary nature of most models – so much so that some authors like C. Bail believe that open-source models devoted to, and controlled by, researchers can help address some of these challenges.

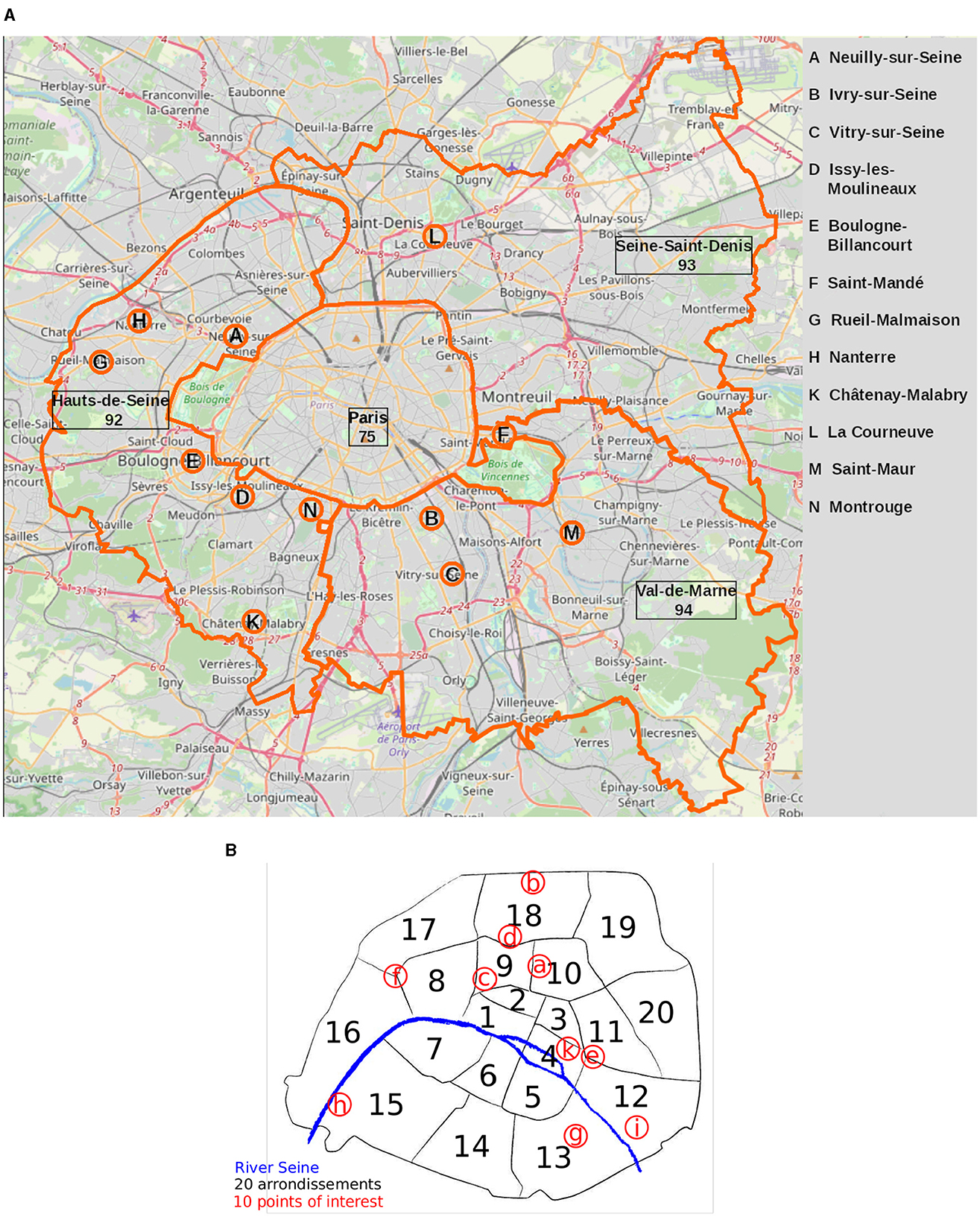

Overall, AI has slowly entered the toolbox of the sociologist, and except for some applications that are now commonplace (from automated transcriptions to NLP), its use has not completely revolutionised practices. This pattern is not exclusive to sociology. My own study of the diffusion of AI in science until 2021, as part of the ScientIA project led by F. Gargiulo, showed limited penetration in almost all disciplines, although the last two years have seen a major acceleration. The opportunities that AI offers are promising, although a lot are more hypothetical than real at the moment. We still see calls that invite sociologists and social scientists to embrace AI, but the number of realizations is still small. Almost all applications devote time to consider the epistemological, methodological, and substantive implications. A question that often emerges concerns the nature of bias. The AI-as-object perspective challenges the language of bias, and we see the same here, though from a different perspective. There’s still no shared definition of bias (or any substitute for this term). More generally, patterns are similar in qualitative and quantitative studies. The guest-editors of last year’s special issue of Sociologica suggest that, like digital methods 10-15 years ago, generative AI is supporting a move beyond the traditional qualitative/quantitative divide.

Concluding, both Sociology-of-AI and Sociology-with-AI exist and are important, but they are not well integrated. This is one of the bottlenecks for the development of the methodological toolbox of sociology, but also for the development of an AI that is useful and positive for people and societies. In part, this may be due to lack of adequate (technical) training for part of the profession, or to the absence of guidelines (for ethics and/or scientific integrity). But perhaps, the real obstacles are less immediately visible. One of them is the difficulty to judge the uptake of AI in our discipline: are we just feeding the hype if we use it? Or are we missing a major opportunity to make sociology more relevant/stronger if we don’t? The other concerns the questions and issues that go beyond the specificities of sociology. How to continue interacting with other disciplines, while upholding the distinctive contribution of sociology?