On Monday, 7 December 2015 at Telecom ParisTech, I was discussant at a seminar by New School scholar Trebor Scholz on “Unpacking Platform Cooperativism“.

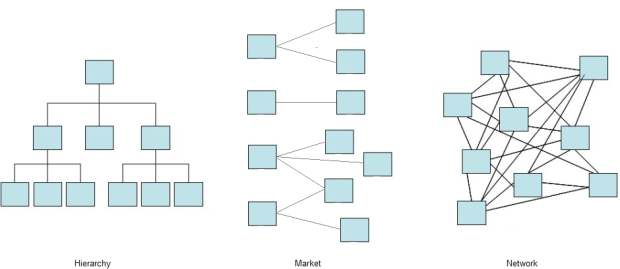

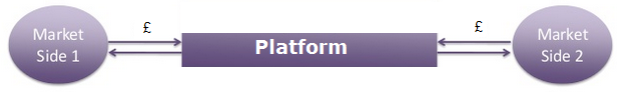

Internet platforms carry an unprecedented potential of value creation, exploiting the extraordinary power of data and algorithms to extract and distribute information to an extent never seen before. Information, we know since Hayek’s times, is the fuel that keeps markets going, that eliminates “lemons” and ensures an ever-better coordination between buyers and sellers, borrowers and lenders, or landlords and tenants. At the same time, the internet has channeled the dream of a viable non-market society, since Rheingold’s 1993 revival of the “community” and Barbrook’s 1998 “hi-tech gift economy“. So, can we put this informational efficiency to the service of a more humane economy, based on relationships, solidarity and reciprocation, rather than on the sheer market system?

The so-called “sharing economy” suggests answers, but also displays a tension: the efforts of myriad grassroots associations to develop collaboration as a value and a practice, sharply contrasts the spectacular growth of firms like Airbnb and Uber, now large multinationals, and their alleged cavalier attitude to anti-trust regulations and workers’ rights. If some say Uber is not really about sharing and collaboration, it is difficult to draw the line.

This ambiguity is fostered by a public discourse that focuses on the sharing of assets – the spare room in your home, or a sit in your car – that digital platforms enable. Asset-sharing has economic and social appeal: it increases efficiency by preventing assets from lying idle, while reducing waste, shifting emphasis away from consumerist values (“access is better than ownership“), and facilitating sociality beyond mere consumption.

But it is often forgotten that asset-sharing does not produce value by itself: it involves extra labour. In economic jargon, capital and labour and complementary production factors. In practice, if you want to put your spare room on Airbnb, you must produce an ad, monitor your message inbox and reply swiftly. You must clean the room and do the laundry before and after a guest’s visit. You must show your guests around when they arrive.

More importantly, the very opportunity of asset-sharing changes the incentives that shape labour supply – people’s willingness to sell their time and effort against a payment. Because of the expected compensation, some people will renounce use of a (non-spare) room to accommodate visitors instead, and others will do more journeys to drive passengers around – so it’s not really about sharing unused assets, it is about self-employment and starting a micro-business. A work opportunity as a complement to (and sometimes a substitute for) a main job.

This is where debates on internet platforms and the sharing economy rejoin the growing literature on digital labour — and where the contribution of Trebor Scholz is illuminating. Where others see assets (ie, capital), he sees labour. He shows us that the bottlenecks here are about labour, not capital, and that the success — be it economic or social– of the sharing economy is closely tied to the destiny of labour. Whether it appears on the surface as self-employment, micro-entrepreneurship or salaried work, doesn’t really matter. Trebor reminds us of Marx’s fundamental principle that production relations are central to our (capitalist) society, and value generation rests ultimately on labor. If this very crucial part of the human experience goes wrong, even the best side of the sharing economy – the one that endorses trust, reciprocity, and zero-waste – may fail to perform any transformative effects on society.

Continue reading “Discussing platform cooperativism”

Antonio A. Casilli and I carried out a study during the OuiShare Fest 2016, a major international get-together of the collaborative economy community that took place in Paris on 18-21 May 2016.

Antonio A. Casilli and I carried out a study during the OuiShare Fest 2016, a major international get-together of the collaborative economy community that took place in Paris on 18-21 May 2016. member/volunteer, you were asked to complete a brief questionnaire in paper format that was handed out to you upon arrival at the Fest.

member/volunteer, you were asked to complete a brief questionnaire in paper format that was handed out to you upon arrival at the Fest.