Our inter-disciplinary, inter-institutional SPS seminar (Paris Seminar on the Analysis of Social Processes and Structures) has just started its second edition! Its purpose is to take stock of the debates within the international scientific community that have repercussions on the practice of contemporary sociology, and that renew the ways in which we construct research designs, i.e., the ways in which we connect theoretical claims, data collection and methods to assess the link between data and theory. Several observations motivate this endeavor. Increasing interactions between social sciences and disciplines such as computer science, physics and biology outline new conceptual and methodological perspectives on social realities. The availability of massive data sets raises the question of the tools required to describe, visualize and model these data sets. Simulation techniques, experimental methods and counterfactual analyses modify our conceptions of causality. Crossing sociology’s disciplinary frontiers, network analysis expands its range of scales. In addition, the development of mixed methods redraws the distinction between qualitative and quantitative approaches. In light of these challenges, the SPS seminar discusses studies that, irrespective of their subject and disciplinary background, provide the opportunity to deepen our understanding of the relations between theory, data and methods in social sciences.

Author Archives: paolatubaro

Recent ethical challenges in social network analysis (RECSNA17)

Research on social networks is experiencing unprecedented growth, fuelled by the consolidation of network science and the increasing availability of data from digital networking platforms. However, it raises formidable ethical issues that often fall outside existing regulations and guidelines. New tools to collect, treat, store personal data expose both researchers and participants to specific risks. Political use and business capture of scientific results transcend standard research concerns. Legal and social ramifications of studies on personal ties and human networks surface.

We invite contributions from researchers in the social sciences, economics, management, statistics, computer science, law and philosophy, as well as other stakeholders to advance the ethical reflection in the face of new research challenges.

The workshop will take place on 5 December 2017 (full day) at MSH Paris-Saclay, with open keynote sessions to be held on 6 December 2017 (morning) at Hôtel de Lauzun, a 17th century palace in the heart of historic Île de la Cité.

Calendar:

- Submit a 300-word abstract by 15 October 2017.

- Let us know if you wish to be panel discussant or session chair by 20 October 2017 (send to: recsna17@msh-paris-saclay.fr).

- Acceptance notifications will be sent by 31 October 2017.

- Registration is free but mandatory: speakers (and discussants and chairs) should register between 15 October and 15 November 2017, other attendees by 30 November 2017.

Keynote Speakers

José Luis Molina, Autonomous University of Barcelona, “HyperEthics: A Critical Account”

Bernie Hogan, Oxford Internet Institute, “Privatising the personal network: Ethical challenges for social network site research”

Scientific Committee

Antonio A. Casilli (Telecom ParisTech, FR), Alessio D’Angelo (Middlesex University, UK), Guillaume Favre (University of Toulouse Jean-Jaurès, FR), Bernie Hogan (Oxford Internet Institute, UK), Elise Penalva-Icher (University of Paris Dauphine, FR), Louise Ryan (University of Sheffield, UK), Paola Tubaro (CNRS, FR).

Contact us

Email: recsna17@msh-paris-saclay.fr

Webpage: http://recsna17.sciencesconf.org

Twitter: @recsna17

Sharing Networks 2017: pen-and-paper fieldwork in a big data world

I’m excited to report that earlier this month, I ran the second wave of data collection for our Sharing Networks research project at OuiShare Fest 2017!

To understand how people form and reinforce face-to-face network ties at such an event, I fielded a questionnaire with the help of a committed and effective team of co-researchers. It is a “name generator” asking respondents to name those they knew before the OuiShare Fest, and met again there (“old frields”); and those they met during the event for the first time (“new contacts”). Participants then have to choose those among their “old” and “new” contacts, that they would like to contact again in future for joint projects or collaborations.

Interestingly, my good old pen-and-paper questionnaire still gives a lot of insight that digital data from social media cannot provide – just like a highly computer literate community such as this feels the need to meet physically in one place every year for a few days. Like trade fairs that flourish even more in the internet era, the OuiShare Fest gathers more participants at each edition. They meet in person there, which is why they are to be invited to respond in person too.

Continue reading “Sharing Networks 2017: pen-and-paper fieldwork in a big data world”

Sharing Networks study 2017: Moving online!

I’m so excited that earlier this month, I ran the second wave of data collection for my Sharing Networks research project at OuiShare Fest 2017!

The study aims to map the collaborative economy community that gathers at OuiShare Fest, looking at how people network and how this fosters the emergence of new trends and topics.

During the event, a small team of committed and effective co-researchers helped me interview participants. We used a questionnaire with a “name generator” format, typically used in social network analysis to elicit people’s connections and reconstitute their social environment.

Specifically, we asked respondents to name people they knew before the

OuiShare Fest, and met again there (“old friends”), and people they met during the Fest for the first time (“new contacts”). Then we asked them to choose, from among the “old” and “new” they had named, those they would like to contact again with soon, for example for joint projects or collaborations.

I am very happy with the result: 160 completed interviews over three half-days! But it is still not enough: participants to the Fest were much more numerous than that, and in social network analysis, it is well-known that sampling is insufficient, and one needs to get as close to exhaustiveness as possible.

Therefore, for those OuiShare Fest 2017 participants that we did not manage to interview, there is now an opportunity to complete the questionnaire online.

If you were at the Fest and we did not talk to you, please do participate now! It takes less than 8 minutes, and you will help the research team as well as the organization of the Fest.

Many thanks to the team of co-researchers who helped me, the OuiShare team members who supported us, and all respondents.

More information about the Sharing Networks study is available here.

Highlights from results of last years’ Sharing Networks survey are available here.

Networks in the collaborative economy: social ties at the OuiShare Fest 2016

The OuiShare Fest brings together representatives of the international collaborative economy community. One of its goals is to expose participants to inspiring new ideas, while also offering them an opportunity for networking and building collaborative ties.

At the 2016 OuiShare Fest, we ran a study of people’s networking. Attendees, speakers and team members were asked to complete a brief questionnaire, on paper or online.Through this questionnaire, we gained information on the relationships of 445 persons – about one-third of participants.

Ties that separate: the inheritance of past relationships

For many participants, the Fest was an opportunity to catch up with others they knew before. Of these relations, half are 12 months old at most. About 40% of them were formed at work; 15% at previous OuiShare Fests or other collaborative economy experiences; 9% can be ascribed to living in the same town or neighborhood; and 7% date back to school time.

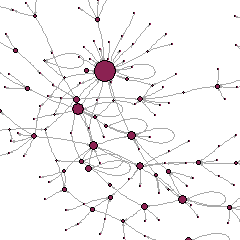

Figure 1 is a synthesis of these “catching-up-with-old-friends” relationships, in the shape of a network where small black dots represent people and blue lines represent social ties between them. At the center of the graph are “isolates”, participants who had no pre-existing relationship among OuiShare Fest attendees. The remaining 60% have prior connections, but form part of separate clusters. Some of them (27%) form a rather large component, visible at the top of the figure, where each member is directly or indirectly connected to anyone else in that component. There are also two medium-sized clusters of connected people at the bottom. The rest consists of many tiny sub-groups, mostly of 2-3 individuals each.

Ties that bind: new acquaintances made at the event

Participants told us that they also met new persons at the Fest. Figure 2 enriches Figure 1 by adding – in red – the new connections that people made during the event. The ties formed during the Fest connect the clusters that were separate before: now, 86% of participants are in the largest network component, meaning that any one of them can reach, directly or indirectly, 86% of the others.

Continue reading “Networks in the collaborative economy: social ties at the OuiShare Fest 2016”

Open Data: What’s new in 2017?

I am now in Montréal, where I participated, last Friday, in a panel on Open Data at “Science & You” international conference. It was interesting for me to reflect on how the picture has changed since my previous panel on the same topic – in Kiev in 2012. Back then, we were busy trying to convince public administrations that data opening was good for transparency and could help improve services to communities. Since then, a lot of attempts have been made in numerous countries – local authorities often pioneering the process, followed only later by central governments (one example cited in my panel was Québec City). What is made open is typically information from public registers (first names of newborns, records of road accidents) and increasingly, from technological devices and sensors (bus traffic information).

There are some conditions to be met for a dataset to be said “open”:

- Technically, it needs to be “raw”, detailed, digital and reusable. The French Interior Ministry released results of the first round of the recent presidential elections within a few days, at polling station level. This is sufficiently detailed (with over 69,000 polling stations throughout the country), raw (allowing aggregations, comparisons etc.), and digital/reusable (so much so that the newspaper Le Monde could develop a user-friendly application to let readers easily check results in their neighborhoods). Some would also insist that “open” data should be released in non-proprietary formats (better .csv than .xls, for example).

- Legally, the data must come with a license that allows re-use by third parties (typically within the Creative Commons family). Ideally, no type of reuse should be ruled out (including somewhat controversially, commercial / for-profit reuse).

- Economically, the data should be available to all for free (or at least with minimal charges if data preparation requires extra work or expenses).

If in the past few years, a lot of thought has been devoted to the “ideal” conditions for data opening and how this would positively affect public service, the data landscape has now significantly changed.

Visualisation, mixed methods and social networks: what’s new

This morning, we had a plenary on “Visualisation and social networks in mixed-methods sociological research” at the British Sociological Association conference now going on in Manchester. This session, organized by the BSA study group on social networks that I convene with Alessio D’Angelo (BSA SNAG), builds on a special section of Sociological Research Online that we edited in 2016. Alessio and I chaired and had four top-flying speakers: Nick Crossley, Gemma Edwards (both at the University of Manchester), Bernie Hogan (Oxford Internet Institute) and Louise Ryan (University of Sheffield).

This morning, we had a plenary on “Visualisation and social networks in mixed-methods sociological research” at the British Sociological Association conference now going on in Manchester. This session, organized by the BSA study group on social networks that I convene with Alessio D’Angelo (BSA SNAG), builds on a special section of Sociological Research Online that we edited in 2016. Alessio and I chaired and had four top-flying speakers: Nick Crossley, Gemma Edwards (both at the University of Manchester), Bernie Hogan (Oxford Internet Institute) and Louise Ryan (University of Sheffield).

Each speaker briefly presented a case study that involved visualization, and all were great in conveying exciting albeit complex ideas in a short time span. What follows is a short summary of the main insight (as I saw it).

Continue reading “Visualisation, mixed methods and social networks: what’s new”

Science XXL: digital data and social science

I attended last week (unfortunately only part of) an interesting workshop on the effects of today’s abundance and diversity of digital data on social science practices, aptly called “Science XXL“. A variety of topics were discussed and different research experiences were shared, but I’ll just summarize here a few lessons learned that I find interesting.

- Digital data are archive data. Data retrieved automatically from the digital traces of individual actions, such as those mined from the APIs of platforms such as Twitter, are unlike survey data in that they were not originally recorded for research purposes. The researcher must select relevant records on the basis of some understanding of the conditions under which these data were produced. Perhaps ironically, digital data share these characteristic with data from historical or literary archives.

- Digital data are not necessarily “big”, in the sense that their volume is often small (at least in social science research so far!), even though they may share other characteristics of big data such as velocity (being generated on the fly as people use digital platforms) or variety (being little or not structured).

- Digital data can help fill gaps in survey data, for example when survey sampling is not statistically representative: detail and volume can provide extra information that supports general conclusions.

- Non-clean data, outliers and aberrant observations may be very informative, revealing details that would escape attention if researchers focused only on the average or center of the distribution (the normal law cherished in classical statistical approaches). Special cases are no longer a prerogative of qualitative research.

- Data analysis is a key ingredient of “computational social science” a field that is growing in importance after an initial phase in which it was largely confined to agent-based simulation and complexity theory.

A cooperative approach to platforms

I was yesterday at a nice and interesting conference in Brussels on “How to coop the collaborative economy“, organized by major actors of the Belgian cooperative movement and building on the experience of a growing network of persons and organizations to enhance a cooperative view of the internet. Several themes in connection with my studies of the collaborative economy emerged, and I’d like to summarize here what were, in my view, the main lessons learned of the day.

New: Paris Seminar on the Analysis of Social Processes and Structures (SPS)

Together with colleagues Gianluca Manzo, Etienne Ollion, Ivan Ermakoff, and Ivaylo Petev, I organize a new inter-institutional seminar series in sociology.

This new Social Processes and Structures (SPS) Seminar aims to take stock of the debates within the international scientific community that have repercussions for the practice of contemporary sociology, and that renew the ways in which we construct research designs, i.e., the ways in which we connect theoretical claims, data collection and methods to assess the link between data and theory. Several observations motivate this endeavor. Increasing interactions between social sciences and disciplines such as computer science, physics and biology outline new conceptual and methodological perspectives on social realities. The availability of massive data sets raises the question of the tools required to describe, visualize and model these data sets. Simulation techniques, experimental methods and counterfactual analyses modify our conceptions of causality. Crossing sociology’s disciplinary frontiers, network analysis expands its range of scales. In addition, the development of mixed methods redraws the distinction between qualitative and quantitative approaches. In light of these challenges, the SPS seminar discusses studies that, no matter their subject and disciplinary background, provide the opportunity to deepen our understanding of the relations between theory, data and methods in social sciences.

The inaugural session took place on 20 November 2016; the “regular” series starts this Friday, 27 January, and will continue until June, with one meeting per month.

All sessions take place at Maison de la Recherche, 28 rue Serpente, 75006 Paris, room D040, 5pm-7pm. All interested students and scholars are welcome, and there is no need to register in advance.

Continue reading “New: Paris Seminar on the Analysis of Social Processes and Structures (SPS)”