A new book is just out, co-authored by myself and Antonio A. Casilli: a synthesis of our 5-odd years research on the self-styled internet communities, blogs and forums of persons with eating disorders. For years, lively controversies have surrounded these websites, where users express their distress without filters and go as far as to describe their crises, their vomiting and their desire for an impossibly thin body – thereby earning from the media a reputation for “promoting anorexia” (shortened as “pro-ana”). In France, an attempt to outlaw these online spaces last year was unsuccessful, not least because of our active resistance to it.

A new book is just out, co-authored by myself and Antonio A. Casilli: a synthesis of our 5-odd years research on the self-styled internet communities, blogs and forums of persons with eating disorders. For years, lively controversies have surrounded these websites, where users express their distress without filters and go as far as to describe their crises, their vomiting and their desire for an impossibly thin body – thereby earning from the media a reputation for “promoting anorexia” (shortened as “pro-ana”). In France, an attempt to outlaw these online spaces last year was unsuccessful, not least because of our active resistance to it.

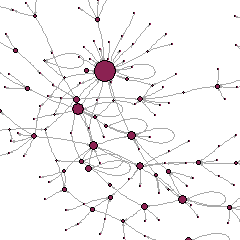

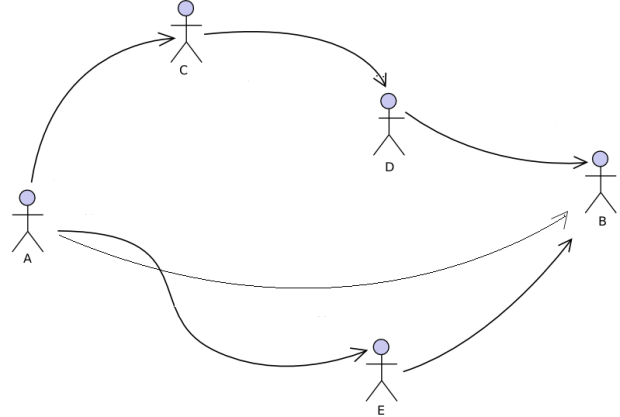

The book tells the story of our discovery of these communities, their members, their daily lives and their social networks. Ours was the first study to go beyond just contents, and discover the social environments in which they are embedded. We explored the social networks (not only online relationships, but day-to-day interactions at school or work, in the family, and among friends) of internet users with eating disorders, and related them to their health. The results defy received wisdom – and explain why banning these websites is not the right solution.

Internet deviance or public health budget cuts?

It turns out that “pro-ana” is less a form of internet deviance than a sign of more general problems with health systems. Joining these online communities is a way to address, albeit partially and imperfectly, the perceived shortcomings of healthcare services. Internet presence is all the more remarkable for those who live in “medical deserts” with more than an hour drive to the nearest surgery or hospital. At the time of the survey in France, a number of areas lacked specialist services for eating disorder sufferers.

These people do not always aim to refute medical norms. Rather, they seek support for everyday life, after and beyond hospitalisation. These websites offer them an additional space for socialisation, where they form bonds of solidarity and mutual aid. Ultimately, the paradoxical behaviours observed online are the result of underfunded health systems and cuts in public budgets, that impose pressure on patients. The new model of the ‘active patient’, informed and proactive, may have unexpected consequences.

A niche phenomenon with wider repercussions

In this sense, “pro-ana” websites are not just a niche phenomenon, but a prism through which we can read broader societal issues: our present obsession with body image, our changing relationships with medical authorities, the crisis and deficit of our publich health systems, as well as the growing restrictions to our freedom of expression online.

Continue reading “The “pro-ana” phenomenon: Eating disorders and social networks”